28/03/2018

Alexis Clerc, sj - The Irish Monthly - Vol 8 - n.83 - 1880

Source: The Irish Monthly, Vol. 8, No. 83 (May, 1880), pp. 271-277 Published by: Irish Jesuit Province

ALEXIS CLERC, S.J.

BY THE EDITOR.

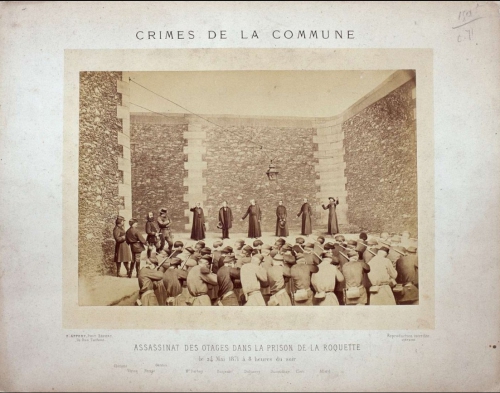

ENNIUS, I think, congratulated himself on having two souls because he knew two languages, Latin and Oscan. Those of us who know French ought to nourish our souls on a food which the language that we speak does not furnish in sufficient variety and abundance. We ought to read as many as we can of the holy and invigorating biographies to be found in contemporary French literature. Of these one of the latest specimens is Father Charles Daniel’s "Alexis Clerc, Marin, Jésuite, et Otage de la Commune, fusillé à la Roquette, le 24 Mai 1871." Its charm lies chiefly in the minuteness of its details and in the many extracts from Pere Clerc’s correspondence and private papers. It must not be judged, therefore, from the following summary of a few of its pages here and there.

Alexis Clerc was born at Paris on the 12th of December, 1819, and was baptised on the following day. His father had been carried away by the evil principles which have done so much harm to the middle class of Paris especially; and this made still sadder the loss which he suffered when thirteen years old in the death of his pious mother. The years of his education in state schools and at the University led him farther and farther from the practice of religion. One of his old school-fellows says he was distinguished for his gaiety of character and "sa facile intelligence de l’x" – that is to say, his devotion to unknown quantities, his success in mathematical studies. When the time came for choosing a calling in life, he selected the navy, and began by taking his place as a midshipman on board the Triomphante, which sailed from Brest, for the Southern Ocean, on the 22nd of October, 1841. At this time his thoughts were far away from Mary, Star of the Sea, and from her Divine Son; but the first strong impulse of grace came upon him during his first voyage when he was struck with the effects wrought by Christianity among the natives of the Gambier Isles. A good young comrade, Claude Joubert, with whom he became intimate on board the Charte, and who afterwards died during his preparation for the priesthood, was another instrument used by God for his conversion; but the process was slow and was to stretch still over many years.

The frigate La Charte, which we have just named, brought Clerc home to France, after four years’ service, during which he had seen Brazil, Chili, Peru, the Marquisas, the New Hebrides, and many other "foreign parts," and had reached his twenty-sixth year. He spent in France, partly in Paris, and partly at Toulon, the months between October, 1845, and May, 1846, without resuming or rather beginning the practice of religion, yet drawing nearer to the decisive step. The book which had the largest share at this crisis in convincing his intellect was the Démonstration Évangélique of Duvoisin.

In May, 1846, he sailed for the African station in the war steamer Caiman, of which the chief duty was to hinder the slave trade; and it was on the African coast that he himself made good his escape from the slavery of sin and unbelief. He made his general confession to one of the missionaries to the kingdom of Dahomey and received Holy Communion for the first or almost the first time. Writing to his brother, who was a year or two older and who became a practical Catholic about the same time, he thinks of the mother they had lost when he was a boy of thirteen years. “Il nous faut aller tous vers une pauvre sainte femme qui nous tend les bras là-haut. Elle nous appelle, pour sûr, de tous ses efforts." This great event took place on his 27th birthday. He takes note of this in telling the good news to Claude Joubert "J’ai reçu l’absolution, presque moment pour moment vingt-sept ans après ma naissance."

In the letter from which we take this phrase an illustration is given of the accelerated force and speed of the passions when once yielded to, which we may try to turn into English. "Man’s soul is like a stone planted firmly on the side of a mountain. Shake it little by little, make it at last with great difficulty give but one turn, it will continue to roll down of its own accord, slowly at first, and perhaps you could still stop it; but soon its course becomes impetuous, no obstacles can any longer stay its progress, it clears them all with huge leaps which increase still more its rapidity; it crushes, it drags down everything that it meets, and at last flings itself as if with ever-increasing fury into the depths of the abyss."

After his return from the African coast M. Clerc was stationed at Lorient. His confessor when at Paris was Monseigneur de la Bouillerie, then Vicar-General of Paris, since Bishop of Carcassonne and Coadjutor to the Archbishop of Bordeaux[1]. We name him, not only out of gratitude for his patient kindness towards this returned prodigal, but also out of gratitude to the author of a most devout and engaging little book which has gone through nearly fifty editions – "Méditations sur l’Eucharistie." From this date, while devoted more steadily than ever to his profession and while keeping up his jovial character with his comrades, Alexis Clerc declared himself frankly and firmly, but modestly, a practical and uncompromising Catholic. Of all books in the world the one that he chose as his constant companion henceforth was the Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas. The late Encyclical of Leo XIII., Æterni Patris, would have been a joy to his heart; for he never faltered in his allegiance to the Angelic Doctor; and from the prison which his native Paris has in store for him, we shall see him begging for two books as solaces for his captivity – the Bible and the Summa.

I do not recollect who wrote the lines, or of whom they were first written, but they are applicable to the uneventful lives of many who are known to posterity only through their writings:—

"That he was born, it cannot be denied;

He ate, drank, slept, wrote deathless works – and died."

Substituting for the "I deathless works" good works of another kind, which in their effects and in their rewards are more surely immortal, this couplet holds true of many saintly and many holy and useful lives, such as the one now before us, to which another couplet of about the same date may also be applied with a special meaning:—

"He taught us how to live, and-oh! too high

The price of knowledge ! – taught us how to die.

For indeed Father Clerc’s Life would hardly have been written, even in France, but for the strange death which was to bring it to a close. To the chain of graces, of which this heroic death was the last link, God went on adding link after link during the years which Alexis Clerc continued to spend in the difficult circumstances in which the grace of the conversion had found him out. In spite of certain leanings towards the religious state, Father de Ravignan advised him, after a retreat made at the Rue de Sèvres, to persevere still in the naval profession. A voyage to China and Japan in the Cassini, chiefly undertaken for the advantage of the Chinese missions, occupied several years. The history of these years includes several most touching accounts of the conversions which the brave young lieutenant wrought by word and example, furnished by the midshipmen themselves amongst whom he exercised this novel apostleship. Here, as all through this book, the vivid interest of Père Daniel’s pages is due to the very minute and simple details which he ventures to divulge, but always with good taste and discretion. A mere naming of persons and places would not serve our purpose; so we pass over this very meritorious part of our friend’s life, as also the humble, prudent, and persevering zeal with which he devoted himself to every sort of good work, especially as a member of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, while on the home stations at Brest and at the mouth of the Loire.

We have called him our friend, for we spent two years in close intimacy with him at Laval about five years before his death. We are able to confirm the testimony given in the book on which this sketch is founded, to the simplicity, kindness, cheerfulness, and quiet power of his amiable and manly character, as well as to guarantee the fidelity of the description of his personal appearance which might remind one a little of that Celestial Empire which had occupied so much of his working years. "Petit de taille, Clerc n’était pas beau, du moins dans le sens grec du mot, et son visage aux contours anguleux aurait offert un modèle assez ingrat à la statuaire. L’extrême mobilité de ses traits trahissait sur l’heure toutes ses impressions; son œil de feu et sa voix vibrante annonçaient une âme aussi enthousiaste qu’énergique."

But Pere Clerc was already Père Clerc and had been in the Society of Jesus before that sojourn at Laval to which we have just referred. After his last long "campagne" – which refuses to be translated into campaign and which extended over three years and a half – he threw up his naval commission and entered the Jesuit noviceship at St. Acheul near Amiens, there carrying out with literal fidelity the resolution he had written down on paper after a little retreat made the year before at Zi-Ka-wei in China: "After a very few days at Paris I will go to the novitiate which shall be assigned to me." But it will edify the reader to give the reasons that led up to this very practical conclusion. Lieutenant Clerc, in his retreat near Shanghai, put three questions to himself and set down the pros and cons in parallel columns, the cons being placed on the left. However, as the left column after the first two or three lines is a complete blank, and as our printer – like nature in the old philosophy – "abhors a vacuum," we weld the answers together and abandon the tabular form. The first question is, "Must I aim at religious perfection?" "It is not necessary to salvation, but it is much safer. It is perhaps above my power to persevere; but nothing is impossible to God, and the days slip past one by one. If my courage should fail in an enterprise which is not necessary, it will be rendered more feeble for what is absolutely necessary; but not to undertake it at all after taking it into consideration, is to be beaten without a battle. To strive after perfection is nobler and more agreeable to our Lord. The interior voice of conscience which reproaches us for relaxations which are not sins, is the voice of our Lord jealous for my perfection. Our Lord loathes lukewarm souls. He to whom more has been pardoned ought to feel more gratitude. Therefore I must and will strive after religious perfection." He next proposes to himself the question, whether in order to devote himself to the pursuit of perfection he ought to enter the religious state; and he decides in the affirmative by fourteen reasons against one. And finally he determines to try and entitle himself to the two initials affixed to his name in the heading of this sketch, for six reasons which in other circumstances might well have justified another choice, one of them being that "Ia Compagnie a pour le salut et la perfection de ses enfants les plus admirables et minutieuses solicitudes."

The first of these admirable means provided in the most minute details by the new spiritual Mother, into whose arms Alexis Clerc had thrown himself, was to bury him for two years in the happy hidden life of the novitiate. The fervour and thoroughness with which he began he maintained to the end. When he was just forty years of age he was ordained priest, though his study of dogmatic theology, instead of being hastened on; had to be postponed in order that his practical experience and mathematical knowledge might be turned to account in the famous school of St. Genevieve in the Rue Lhomond which some will recognise better by its old name of the Rue des Postes. And yet, this ex-officer of the French navy, now a priest of 44 years of age, spends four full years in theological studies, going through the routine of class-work with all the docility, punctuality and earnestness which might edify us in a student under age for subdeaconship.

Both before and after this period of theological training Father Clerc had many opportunities of satisfying the yearnings of his priestly zeal by working for the direct sanctification of souls. Yet not only before but also after these four years at Laval, his chief work was the preparing of classes for the governmental examinations, especially in connection with his old department, la marine. In protesting against the Ferry Law, the ex-pupils of the École-Saint-Geneviève told the Deputies lately that their beloved school had in the twenty-five years of its existence passed in these and similar public examinations 2,283 candidates. Modestly and solidly Alexis Clerc did his share of this hard, wasting work, exercising on many souls, meanwhile, a holy influence, to which most beautiful and affecting testimonies are given in Pere Daniel’s book, generally in the words of the young men who were the objects of his untiring and affectionate zeal.

Father Clerc was fifty years old when he was sent, in October, 1869, to Laon, to go through the Third Year of Probation, which, coming after studies and priesthood, is intended to finish the spiritual training begun in the two years’ noviceship. He was often heard to congratulate himself that “un vieux comme lui, " an old fellow like him," should enjoy so great a privilege. In one of his notes of meditation at this time he imagines our Lord giving to him as his motto, device, and watchword: Pro corde meo, per ipsum cor meum, et cum ipso et in ipso. "For my Heart, through my very Heart and with it and in it." He made a special consecration of himself to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, saying: "Je crois que cette dévotion donne droit à une effusion immédiate du Sacré-Cœur de Notre-Seigneur dans le nôtre."

When the terrible reverses of the French army at Wissemburg and Reichshoffen and the rest were leading up to the catastrophe of Sedan, the Jesuit Fathers established a military hospital at their college of Vaugirard, on the outskirts of Paris. Father Clerc was placed over it, and this gave him opportunities of the truest charity, humility, and mortification. He was afterwards desired to resume his mathematical classes; for even at that terrible time the young boys cannot be abandoned, and our Parisian schools are transferred to safer places as near as possible to the old quarters. But the dark hour of the Commune came on. Part of that awful story has been hinted at in our sketch of Father Olivaint[2], another of the martyrs of the Commune. We hope that our readers have read or will read it in full in Father de Ponlevoy’s "Acts of the Captivity and Death of the Fathers Olivaint, Ducoudray, Caubert, Clerc, and De Bengy."

Father Faber – who since the beatification of his namesake, Blessed Peter Faber, is not so easily confounded with that first companion of the founder of the Society of Jesus – the brilliant Oratorian has said that St. Ignatius, setting out bodily from Paris in search of spiritual adventures, seems tame to him compared with St. Ignatius preparing the points for his meditation, years after he had received an infused gift of prayer. And somewhat in the same way Father Alexis Clerc, calmly opening the front of his soutane to receive the bullets of his public and official assassins, seems to me less heroic than when studying, during his imprisonment as a "hostage," for his class of mathematics to which, without knowing it, he had bidden a final adieu. Certainly, among the edifying circumstances recorded of his sojourn at Mazas and La Roquette not the least striking is the persistence with which he asks from his friends outside, not only a Bible, breviary, and a Summa of St. Thomas, but also works on analytical geometry in order to prepare more perfectly – he whose mind was saturated with such studies since his boyhood – his mathematical course for his pupils after his release.

But his release came through death; and surely the " three fast friends of the great good man" were his —

"Himself, his Maker, and the angel Death."

The angel Death delivered his message seemingly in rude fashion, but in reality gently, happily, and joyfully. After a month or so of weary waiting and uncertainty, the ruffians of the Commune, seeing their last hour come, determined to massacre these innocent victims. How they did so, we have partly told already in these pages in our brief account of Father Olivaint[3]. We are unwilling to enter again into the horrible and glorious details. The Fathers died like Christian heroes – as they were. Ah! Monsieur Paul Bert, Monsieur Jules Ferry, and you, Monsieur Spuller, you would not – if you have any sense of virtue and honour – you could not feel as you pretend to feel towards the French Jesuits if you but knew intimately such souls as Alexis Clerc.

[1] We are correcting the spelling for « L’Orient » and « Bourdeaux » [Ed. Note 2018]

[2] The Irish Monthly, vol. vii., page 260 (May, 1879).

[3] The Irish Monthly, vol. vii., page 260 (May, 1879).

19:47 Publié dans Actualités, Bibliographie, Biographie, Commune de 1871, Compagnie de Jésus, Eglise catholique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)

16/12/2017

Ecoute et docilité parfaite

Vu sur: https://evangeliser.net/lecoute-docilite-parfaite/

L’écoute et la docilité parfaite

2017-03-10 Geoffroy de Lestrange

Introduction : La difficile écoute …

… d’un aspirant

L’abbé Clerc, jésuite, meurt, martyr de la Commune, le 24 mai 1871, à la prison de La Roquette, avec Mgr Georges Darboy, archevêque de Paris et 30 compagnons. M. Clerc avait été officier naval. Le 16 mai 1871, à la prison de Mazas, il écrit une lettre en réponse à un ami qu’il a converti à bord du « Cassini » et qui l’assure de sa prière. « J’avais l’espérance que Dieu me donnerait la force de bien mourir; aujourd’hui mon espérance est devenue une vraie et solide confiance. Il me semble que je peux tout en Celui qui me fortifie. […] Comme vous aurez une grande part à ce bienfait de la force qu’il m’aura prêtée ! » La conversion de son correspondant n’avait pas été aisée. Les raisons en étaient simples : Des notions de catéchisme, dans un environnement hostile, si bien qu’il communie pour la première fois à douze ans et demi, mais « cette première fois devait, hélas, être presque la dernière, pour un long temps du moins ». Un très fort respect humain : « A la fête de Pâques qui suivit ma première communion, j’étais déjà profondément gâté par le respect humain, et si, à cette occasion, j’approchai une fois de la sainte Table, ce fut à l’invitation des religieuses de l’infirmerie, où je me trouvais dans ce moment, et sans doute le Dieu d’amour ne trouva plus dans mon cœur qu’une bien chétive flamme, trop refroidie déjà pour qu’Il pût l’aviver. De ce jour les ténèbres s’épaissirent de plus en plus autour de mon âme et, après avoir rougi d’abord d’un moment de naïve piété, j’en vins bientôt à me faire une misérable gloire d’afficher l’impiété par mes actes, comme par mes discours. Notre jeune homme passe du collège à l’école préparatoire, puis à l’école navale. A 19 ans, il prend la mer en qualité d’aspirant. Embarqué sur Le Cassini, le bateau compte parmi ses officiers M. Clerc, lieutenant de vaisseau. Devant ses camarades pratiquants, deux ou trois, l’aspirant proclame hautement et bruyamment son impiété. Voguant vers l’île de la Réunion, son navire porte Mgr Desprez, évêque nommé de cette île, avec plusieurs prêtres et des religieuses, et en Chine, Mgr Vérolles, évêque de Mandchourie, ainsi que plusieurs prêtres des Missions étrangères. Seul de tout le personnel, il s’abstient de participer à l’Office de Pâques, « très fier de me voir seul, parmi tant de personnes, complètement exempt de sots préjugés et courageusement indépendant. » Descendu à terre sur une des îles de la terre de Chine, il cueille pourtant des fleurs et les offre à des religieuses qui alors n’auront de cesse de prier pour lui. Au mois de janvier 1853, le vaisseau séjourne dans les eaux de Canton où monte l’abbé Girard, prêtre des Missions étrangères. Celui-ci l’engage à ne pas repousser indéfiniment la grâce divine, puis le confie au lieutenant de vaisseau Clerc. Celui-ci, un soir, alors que le bateau était à l’ancre, arrache à l’aspirant l’aveu du vide douloureux qu’il ressent souvent dans son âme, alors qu’il « prêtait l’oreille » aux leçons d’astronomie à l’école navale, et que l’immensité étoilée qu’il contemple souvent lui fait deviner « au-delà de cette matière immense, mais finie, l’Infini que mon âme avait perdu ». Il lui fait retrouver la foi, les sacrements, la prière.

… des disciples

« Celui-ci est Mon Fils bien-aimé, en qui je trouve Ma joie : écoutez-Le ! » Se pourrait-Il que les trois disciples aient été distraits ? Il semble que oui. Pierre intervient dans le colloque du Seigneur avec Moïse et Elie, sans beaucoup d’attention. L’un des récits de la Transfiguration ose dire qu’ « il ne savait pas ce qu’il disait ». (Lc. 9, 33) De même, l’aspirant est, à sa manière, un distrait, au moins distrait de Dieu…

… du fidèle

Cette distraction est ce contre quoi s’élève le Père éternel. En quoi consiste cette distraction ? C’est ce sur quoi la Transfiguration nous invite à réfléchir.

- Les obstacles à l’écoute de Dieu…

L’injonction d’écouter reporte chacun au récit du Sinaï où Moïse reçoit la Torah et demande au peuple de la mettre en pratique. Benoît XVI dira que « Jésus est la Torah elle-même », (Jésus de Nazareth, éd. Flammarion, 2008, p. 365) qui n’est pas écouté. Il y a une nuance, en français, entre écouter et entendre. « Moïse, dit le Livre des Nombres, entendait la voix qui lui parlait du haut du propitiatoire placé sur l’arche du témoignage, entre les deux chérubins, et il parlait à l’Eternel. » (Nb. 7, 89) On peut écouter distraitement, comme Pierre, mais on ne peut pas entendre distraitement. Soit on entend, soit on n’entend pas.

- Le premier obstacle à l’écoute est la distraction: On écoute, mais, de fait, on n’entend pas. Il arrive, évidemment que la surdité soit matérielle, mais elle est aussi spirituelle.

- Jésus Lui-même fait face à cette surdité : « Pourquoi leur parles-tu en paraboles ? » demandent les disciples à Jésus. A quoi Il répond : « Parce qu’ils voient sans voir et entendent sans entendre ni comprendre. » (Mt. 13, 10. 13) Jésus cite Isaïe pour que Son propos soit bien clair : « L’esprit de ce peuple s’est épaissi : ils se sont bouché les oreilles, ils ont fermé les yeux, de peur que leurs yeux ne voient, que leurs oreilles n’entendent, que leur esprit ne se convertisse et que Je ne les guérisse. » (Mt. 13, 14) En un mot, la distraction est une volonté de ne pas entendre.

- Les disciples du Seigneur font face à cette surdité. Alors que le Père Girard s’entretient avec l’aspirant en lui commentant une lettre qu’il lui a écrite, celui-ci veut « échapper à l’influence pernicieuse » du bon Père. Quelques instants après, il lit à ses camarades réunis, en en faisant des gorges chaudes, la charitable lettre que le prêtre lui avait écrite et commentée.

- Le deuxième obstacle est l’obstination. Le type de l’obstiné, c’est Pharaon. Le Seigneur avertit Moïse que Pharaon n’écoutera pas et ne tiendra aucun compte des prodiges qu’il fera. Il dit même que c’est Lui, le Seigneur qui « endurcira », « appesantira » et fera « s’obstiner » le cœur de Pharaon : « Moi, J’endurcirai son cœur et il ne laissera pas partir le peuple ! » (Ex. 4, 21; 7, 3 ; 9, 12 ; 10, 1, 20 et 27 ; 11, 10 ; 14, 4, 8 et 17). Le Seigneur explique dans l’Evangile comment Il procède avec les obstinés : « A tout homme qui a, l’on donnera et il aura du surplus ; mais à celui qui n’a pas, on enlèvera même ce qu’il a. » (Mt. 25, 30)

- Cette obstination à rejeter les grâces de Dieu est si grave que l’abbé Girard n’hésite pas à avertir l’aspirant. le Père Clerc finira par le convaincre de céder à la grâce. Mais l’aspirant avoue lui-même qu’il a été bien loin dans l’obstination.

- Le troisième obstacle, le plus grave, c’est l’opposition. Alors que tout un vaisseau va à la Messe le jour de Pâques, l’aspirant se sent très fier de se voir seul, « exempt de sots préjugés etcourageusement indépendant. » Il a raison contre tous.

- Le dernier obstacle, c’est la haine. Quand Jésus ressuscite Lazare, Il signe son arrêt de mort. (cf. Jean 11, 46-53) Les chefs Juifs devant ce miracle éclatant, ne se convertissent pas, mais en conçoivent une jalousie extrême, jusqu’à la haine. Ne pas voir, ne pas entendre, ce n’est pas dans la Bible, une simple distraction, c’est s’opposer à Dieu Lui-même.

- « La présence de ces personnes consacrées à Dieu [à bord du bateau] irritait mon humeur antireligieuse », écrit notre aspirant. L’irritation entretenue est bien proche de la haine, dont, l’aspirant, par miracle, a été gardé.

- L’écoute de Dieu…

Le Père céleste « trouve [Sa] joie » en son Fils précisément parce que le Fils écoute Son Père. « Je fais toujours ce qui Lui plaît », dit Jésus. « Quand vous aurez élevé le Fils de l’homme, alors vous saurez que Je Suis et que Je ne fais rien de Moi-même, mais Je dis ce que le Père M’a enseigné, et Celui qui M’a envoyé est avec Moi ; et Il ne M’a pas laissé seul, parce que Je fais toujours ce qui Lui plaît. » (Jn. 8, 29) L’écoute de Jésus consiste ici :

- A ne pas avoir d’initiative propre.

- A être comme le répétiteur du Père : « Je dis ce que le Père M’a enseigné. »

- A faire ce qui plaît au Père.

Conclusion : L’écoute consiste en une docilité parfaite…

En un mot, l’écoute consiste en une docilité parfaite. La source en est la vénération. C’est parce que Jésus vénère le Père qu’Il lui est soumis. Cette vénération est pleine d’affection. Si Jésus, à l’agonie, préfère la volonté du Père à la Sienne, ce n’est pas tant en raison de la grandeur de Dieu, qu’en raison de Son affection pour Lui. La docilité, se laisse faire. C’est l’exemple que nous laisse :

- Joseph. Dans un très beau vitrail de l’église N.D. de Dijon, Joseph est représenté, dormant, appuyé sur son bâton de marcheur. Il dort, mais son cœur veille, (Ct. 5, 2) attentif à écouter ce que le Seigneur, l’Invisible, lui dit en songe, lui parlant comme Il a coutume de le faire avec les prophètes : « S’il y a parmi vous un prophète, c’est en vision que Je me révèle à lui, c’est dans un songe que Je lui parle. » (Nb. 12, 6) Au fiat de Marie (Lc 1, 38) répond, sans un mot, la docilité parfaite de Joseph à tout ce qui lui est demandé : « Joseph fit comme l’ange du Seigneur lui avait prescrit. » (Mt 1,24, Mt 2,14.21)

- François de Sales. On faisait circuler, dans Annecy, une lettre anonyme, l’accusant de prostitution. A la porte de son évêché, on venait le menacer avec pistolets et épées, crier des chansons paillardes, jeter boue et excréments. On amenait une meute de chiens que l’on faisait hurler à la mort, afin d’empêcher son sommeil. Il commandait simplement de « fermer les portes ». Rencontrait-t-il l’un de ses détracteurs, il l’embrassait affectueusement, comme si de rien n’était. S. Jeanne de Chantal lui reprochait de trop « se laisser faire », mais il l’avait appris de Jésus Lui-même qui se « laissait faire » par la soldatesque à la Passion.

Ecouter Jésus, c’est donc se laisser faire par Dieu et par autrui. N’enseignait-il pas à tendre la joue gauche quand on était frappé sur la joue droite ?

Prions : « Seigneur, fais-nous la grâce de T’écouter en nous « laissant faire » par Toi et par notre prochain. Amen. »

Question : Dans quelles situations vous a-t-il semblé que vous écoutiez ?

Suggestion : Aimer à se laisser faire par son prochain.

Oraison jaculatoire : « Me voici, ô Dieu, pour faire Ta volonté ! »

17:28 Publié dans Actualités, Eglise catholique, Prières | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)

24/05/2017

146e anniversaire

16:38 Publié dans Actualités, Commune de 1871 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0)